Updating the Breast Cancer Screening Guidelines

/Why are people up in arms about breast cancer screening? Last month, the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) released updated recommendations for breast cancer screening. These recommendations differ from breast cancer screening guidelines from the American Cancer Society (ACS) and the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG), but ultimately it is the USPSTF guidelines that determine the minimal required coverage for patients insured under the Affordable Care Act. While that means that a subset of patients and providers will feel obligated to default to the USPSTF recommendations, it would be wrong to assume that these are the absolute best recommendations for every woman in America (though it's important to know that by law all health insurances are required to cover annual screening starting at age 40).

When I was a medical student applying for residency, I still recall one of my interview questions at a popular Bay Area residency program: “If your patient comes to clinic with the latest publication on breast cancer screening and asks why you are recommending a different schedule of screening, what would you say?” Naive as I was, my answer was a rather prolonged explanation of how I would need to discuss with my patient the risks and benefits associated with breast cancer screening, and with this information as well as knowledge about the patient’s other medical comorbidities and family history I would help her come up with a screening schedule that best fits her needs and preferences. “No,” responded my interviewer, “you should always tell your patients that you recommend following ACOG guidelines.”

I couldn’t say it then, but I can now: I respectfully disagree.

Breast cancer is the most common cancer diagnosed in American women, and the second leading cause of cancer death (the top cause of cancer related death in women is lung cancer) (source). In the last year, about 232,000 women were diagnosed with breast cancer in the United States, where every woman has about a 12% risk of being diagnosed with the disease in her lifetime (source). In short, breast cancer is a real problem. The good news is that we have a screening tool - mammography - that has actually been proven to decrease mortality. The bad news is that three different leading medical organizations have conflicting recommendations about how to perform breast cancer screening, with recent updates only putting them more at odds with each other. This can become very confusing for both patients and providers, as it is hard to know which organization’s recommendations are the best. But breast cancer screening isn’t just about putting a bunch of numbers into a statistical program and seeing what comes out the other end. Women’s lives are at stake. The truth is that there is no one size fits all program for screening and the decision of when to start screening mammography, and how often to pursue it, needs to take a multifactorial approach.

There are some downsides to screening mammograms. Mammograms can be very uncomfortable, even painful, for women. There is some exposure to radiation with every mammogram (though you get the same amount of radiation on a transatlantic flight as you do getting a mammogram, and it will take 100 mammograms to equal the radiation of a single CT scan). But the more serious concerns are false positives and over-diagnosis.

False positives happen when a mammogram has a suspicious finding that ends up not being cancer. When you have a suspicious finding you have to work it up to determine whether it is cancer or not, and this involves more imaging as well as biopsies. This whole process can be very anxiety provoking for the patient, and oftentimes unnecessarily so. For every 10,000 women between the ages 40 and 49 in a 10 year period, about 12% will have a false positive mammogram. This number decreases with age, to about 9.3% from ages 50-59, and about 8% from ages 60-69 (source).

Over-diagnosis happens when cancer is diagnosed and treated unnecessarily. It is hard to imagine when cancer treatment would be unnecessary, but the truth is that not all cancers are aggressive and rapidly growing. A small number of breast cancers grow very slowly and gradually and would likely never cause a problem if left untreated. But, because we can’t separate these slow growing cancers from the aggressive more dangerous ones, everyone gets treated the same, meaning that some women are undergoing surgeries, radiation, and chemotherapy that they don’t actually need. We don’t really know how frequently this happens, but the best estimates suggest that anywhere from 1 in 3 to 1 in 8 women being treated for breast cancer are being over-diagnosed and over-treated (source).

Of course, the main benefit to getting screening mammograms is that they can help detect breast cancer earlier, even before the tumor is large enough to be felt on a breast exam in many cases. Earlier detection means there is a much higher chance of successful treatment, and that fewer women will die of breast cancer. Over a ten year period, for every 10,000 women screened for breast cancer from age 40-49, there will be 3 fewer breast cancer deaths. This number increases to 8 in women aged 50-59, and 21 in women aged 60-69 (source).

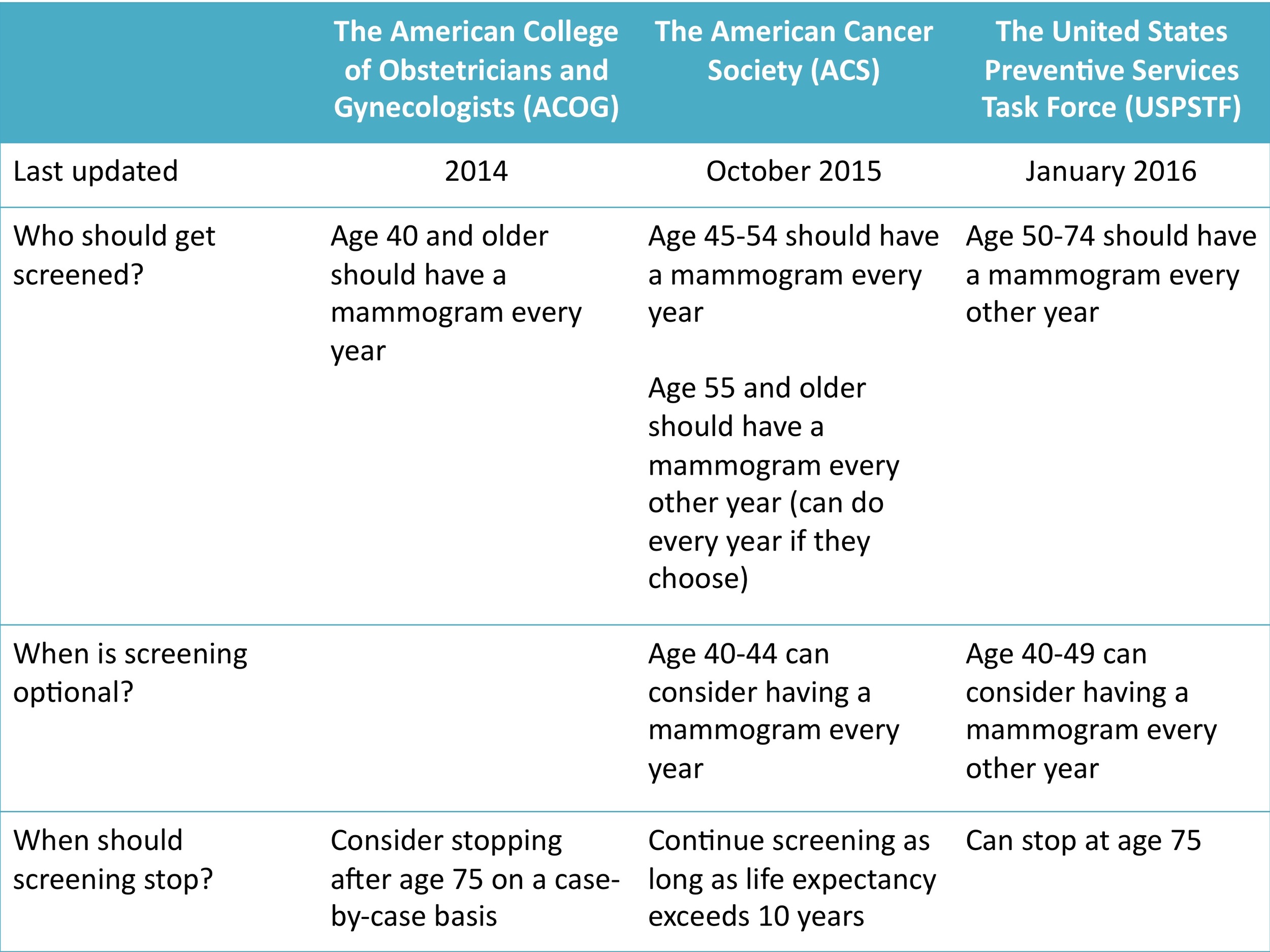

Armed with the exact same data, our three medical organizations all managed to extract different conclusions. The difference lies in the fact that recommendations are all about weighing risks and benefits. Organizations that put a higher weight on mammography risks recommend later starts and/or less frequent studies. Organizations that put more weight on the benefits recommend earlier more frequent screening. The table below summarizes the screening recommendations from ACOG, ACS and USPSTF. Keep in mind that if you are somebody with a family history of breast cancer, it is possible that none of these recommendations apply to you (discuss this with your physician).

Aggregated recommendation guidelines based on the most recent updates

Now that you have all of this information, how do you know what type of breast cancer screening schedule is right for you? This is where you need to have a conversation with your OB/GYN or primary care physician and decide which recommendation (or combination of recommendations) fits your needs best.